This post is also available in Dutch .

Oliver Sacks was a world-renowned neurologist who was born in London in 1933 and died in New York in August of this year. He was best known for his books describing neurological disorders, which shed light on human perception, consciousness, and the mind. Interestingly, when asked for his job title, he would often answer “explorer”.

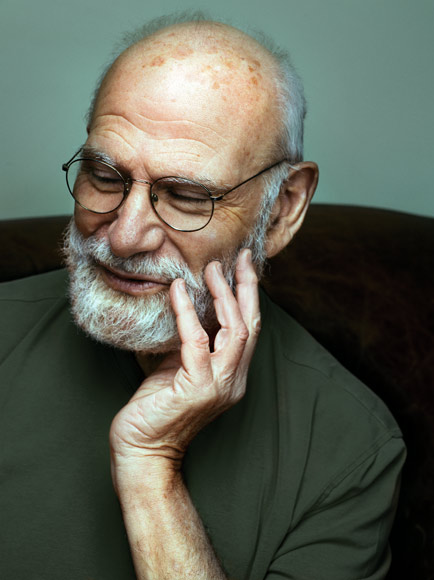

Oliver Sacks. Photo by Maria Popova. Re-used under CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Oliver Sacks. Photo by Maria Popova. Re-used under CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

Sack’s colorful case studies of neurological disorders constituted a journey of discovery, an exploration of the mind that gave us new perspectives on what it means to be human. By introducing us to minds that worked differently than most, Sacks helped the rest of us understand that there is more than one way of experiencing the world. In this way, he broadened our definition of what it means to be “normal”, and helped us appreciate how extraordinary and complex the brain really is.

Sacks never presented a neurological disorder in isolation, but always took care to show it in the context of a patient’s personality and daily life. In his writing, Sacks allowed us to meet the painter who became colorblind but found an uncanny skill for depicting the world in shades of grey; the musician who lost the ability to recognize everyday objects, one day even mistaking his wife for a hat; and autistic individuals with intense talents like drawing scenes photographically from memory.

Sacks was fascinated by different perceptions of reality, including dreams and the hallucinations that people experience during migraines, fever, or schizophrenia (Sacks’ brother Michael was schizophrenic). Captivated by these different views of reality, he recounts once taking mind-altering drugs in the hope of seeing the color indigo, because he could find no outside agreement on what indigo truly looked like.

Sacks also explored the boundaries of consciousness. In 1966, Sacks came across a group of patients in New York’s Beth Abraham Hospital who had lived for decades in a frozen, catatonic state. Sacks “awakened” the patients using the drug L-dopa, which was experimental at the time but is now used in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. He wrote about the different responses of the patients to L-dopa, and their reactions to returning to consciousness in a world they no longer recognized.

Although one might imagine that Sacks would be drawn to a life of research because of his curiosity and observational skills, he describes how activities like dropping his lunch into a centrifuge at the hospital and breaking lab equipment, eventually resulted in laboratory staff telling him to “Get out! Go work with patients”. This turned out to be a lucky piece of advice, setting Sacks on the path towards a long and successful career as a doctor and writer. Sacks’ books and articles describing his explorations of perception, consciousness, and the world of neurological disorders have opened up new insights for millions of readers worldwide.

The field of neuroscience will certainly be a less colorful place without Oliver Sacks. Nevertheless, the lessons that he has taught us will continue to be an invaluable source of inspiration in our quest to understand the inner workings of the brain and what it means to be human. As Sacks himself once said, “In examining disease, we gain wisdom about anatomy and physiology and biology. In examining the person with disease, we gain wisdom about life.”

This blog was written by Lauren Bains, a Postdoc at the Donders Institute. Her research is focused on ultra-high-field MRI. Outside of research, her explorations often take her to the sides of cliffs and tops of mountains.

Edited by Jeroen.