This post is also available in Dutch .

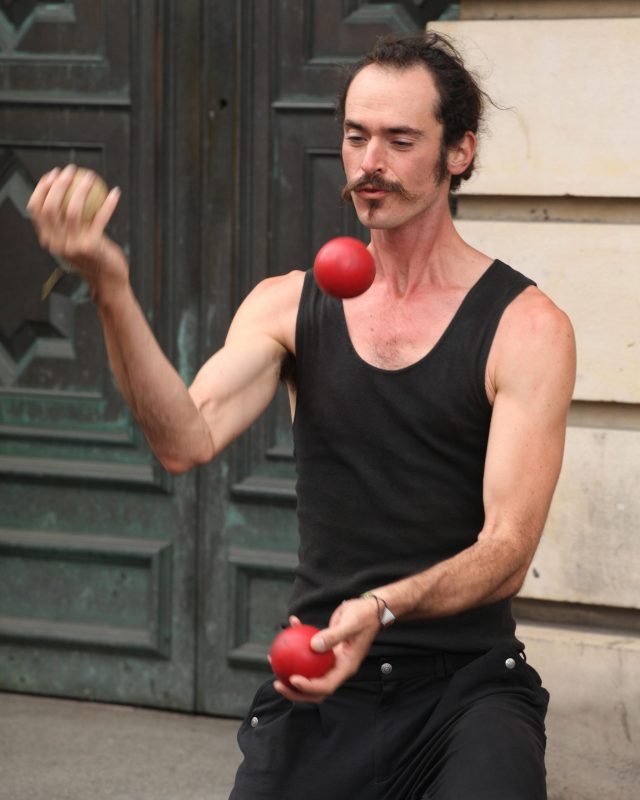

It’s always challenging to learn a new language. But once you speak it fluently, you become an expert in juggling between languages. How does this work?

Are you a multilingual? If you’re able to read this blog and English is not your mother tongue, then the answer is “yes!” You’re a multilingual the moment you’re able to communicate in two languages (respectively referred to as a bilingualism), even if you just started learning the second one1 (and this includes signed languages). And the more languages you know, the more multilingual you become!

Nowadays multilinguals are not so rare. With an increasingly globalizing world, more people tend to adopt English as their second language. You also see people going abroad and becoming fluent in the mother tongue of their new home over time. And in countries like Spain or India, people grow up speaking the multiple languages existent in their home countries. In all of these cases, people seem to be able to switch between languages at the flip of a switch. If you are one of them and do it on a daily basis, you may think it’s quite a banal thing to do, but…

Language switching is fascinating!

The ability to speak more than one language is one of the most studied but still intriguing cases of language research. Switching between the first and second language you may have learnt (respectively labeled in language research as L1 and L2), isn’t like switching between walking and cycling. It’s like switching between worlds, in which each language has its own set of rules and truths. How are we able to switch between both worlds?

Language switching requires language control

Multilinguals use an ability called language control to stick to one language while restricting the other. Language researchers have debated which cognitive skill we use to alternate between languages, and many agree that inhibition is involved. To speak one language, you have to spend energy on inhibiting the other language you know.

The energy cost of inhibiting a language to enable the switching depends on our attachment to each individual language. Let’s think of my case: my L1 is Portuguese, and my L2 is English. Portuguese is my mother tongue and the language I’m most comfortable with. Linguistics tells us that L1 is the language to which we have easier access. Thus Portuguese will require more energy for me to inhibit. English is my second language. Because it is less accessible to me than Portuguese, it will cost less to inhibit it. This applies to me and other multilinguals, especially if they’ve just started learning their L2, L3, L4, and so on.

But what happens when we become very comfortable with our L2?

Then we’re expected to spend less energy when switching between L1 and L2. Back to my personal experience: after spending years working at the Donders Institute, an international environment where English is the first language, I have become more and more used to speaking English. And inhibition has become less and less effortful every time I want to use it. Like me, other experienced multilinguals have become jugglers of languages, switching back and forth between different languages… almost like UN simultaneous interpreters.

Image courtesy of hotblack and Morguefile (CC0 1.0).

But the reality of language inhibition may be more complex.

Despite the many studies that focus on the role of language inhibition in the dance between L1 and L2, this isn’t a consensual topic among language researchers. Some defend that inhibition is present independently of the languages you speak, or your proficiency in those languages. Others claim that highly proficient multilinguals do not really need inhibition to switch between languages. Some even go beyond and suggest that languages can collaborate with each other, instead of competing for a single spot.

Independently of the opinions, the truth is that many exciting scenarios still lie ahead of language researchers in order to reach a full scope of the multilingual reality. And multilinguals across the world will be expectant and excited for what there’s still left to find.

Original language:

English

Author: João Guimarães

Buddy: Eva Klimars

Editor: Monica Wagner

Translator: Jill Naaijen

Editor Translation: Wessel

Hieselaar

Credits: Top image courtesy of gracey and Morguefile (CC0 1.0).

1 While some reserve the term “multilingual” for people who were raised with more than one language (“early, simultaneous bilinguals”), here we adopted a definition that includes people who started learning another language at any point of their lifetime and with different levels of proficiency (sometimes referred to as “second/third language learners”). What type of multilingual are you?