This post is also available in Dutch .

Many researchers argue that large language models (LLMs), including chatbots like ChatGPT, aren’t truly intelligent because they lack embodiment. That is, they have no body to sense or act in the world. In cognitive science, embodiment refers to intelligence arising through a brain interacting with its environment via a body, sensing, acting, and sensing again in a continuous cycle known as the sensory-motor loop. Without this loop, critics argue, AI merely simulates language without understanding it.

Underlying this critique is an assumption that sensing and acting must occur on the same timescale, almost in a 1:1 rhythm. But what if we relax this assumption?

The delayed embodiment: just late, not never, through us.

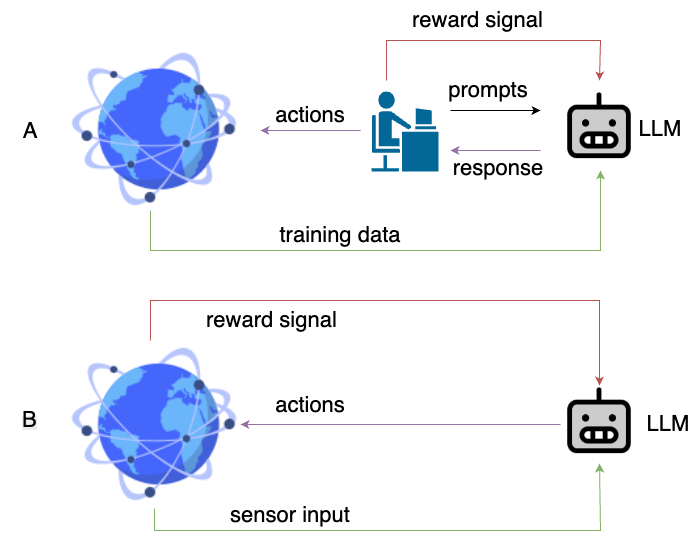

In practice, chatbots do act in the world, just not directly and not at a timescale we typically expect. When we prompt an LLM, the LLM generates a response. That response influences us: maybe a suggestion is followed, maybe an idea is acted upon, or a decision is made. That action changes the world in some way. Eventually, that change flows back into new data used to train the next generation of the LLM. The loop is slow, not at a trivial 1:1 rate, but it’s real.

This human-AI loop is a form of proxy embodiment—where we, the users, serve as its sensors and effectors. The chatbot doesn’t have a body, but it moves through ours just at a different time-scale.Humans also provide reinforcement-like signals to LLMs: liking, disliking or ignoring certain LLM responses. This full cycle closely mirrors the reinforcement learning loop, which is fundamentally embodied.

A. The delayed embodiment loop created of chatbots.

B. Sensor-action loop used in reinforcement learning.

Diagram created using draw.io

Shifting the wall of the Chinese room.

John Searle’s Chinese Room thought experiment describes a person, who doesn’t know Chinese, inside a room, using a rulebook to map symbols. To an outside observer, it looks like the person understands the language. But Searle argues it’s just symbol manipulation, not real understanding. We often put AI in the room and ourselves outside it, then conclude that machines aren’t truly intelligent.

But in today’s world with LLMs, where is the wall of the room? Is the chatbot inside, and we’re outside? Or are we inside with it, co-producing meaning? If humans feed prompts, act on outputs, and generate training data, aren’t we part of the machinery and thus inside the room?This idea echoes Clark and Chalmers’ 1998 thesis on the Extended Mind: when tools are tightly integrated into our cognitive process, like a notebook or a calculator, they become part of the mind. Why not chatbots?

A change of lens.

Perhaps for the first time, a tool is not only embedded in our world but is also complex enough to bear characteristics of natural intelligence. Critics may still argue that the resemblance is loose, LLMs’ building blocks and architectures don’t match any known brain region. But the extraordinary octopus, whose brain diverged from ours over 500 million years ago, reminds us that intelligence doesn’t require structural similarity. It only needs to function within a loop of interaction, adaptation, and meaningful consequence, and be complex enough. And maybe that’s the point: The role a brain component or subpart of an intelligent system plays within a causal loop constrains how it evolves, artificial or not. Systems solving similar problems may converge in form, and we’re already seeing signs. fMRI studies show LLM hidden layers align with human brain activity during language tasks. These models weren’t built to mimic us, yet their internal representations reflect how we process stories and meaning. Maybe the question isn’t whether chatbots are intelligent, maybe it’s whether we’ve become intelligent with them.

Author: Siddharth Chaturvedi

Buddy: Amir Homayun Hallajian

Editor: Xuanwei Li

Translation: Natalie Nielsen

Editor Translation: Lucas Geelen