This post is also available in Dutch .

Rhythms are all around us. If you’re listening to music right now, it probably has a ‘beat’ you can clap along to, and a structure – verse, chorus, verse – that goes around in a cycle. In fact, rhythms exist at all speeds, from the very fast (a hummingbird’s wing) to the very slow (the seasons). Rhythms exist even in your brain, and measuring them can help us understand how different parts of the brain work together.

The orchestra of the brain

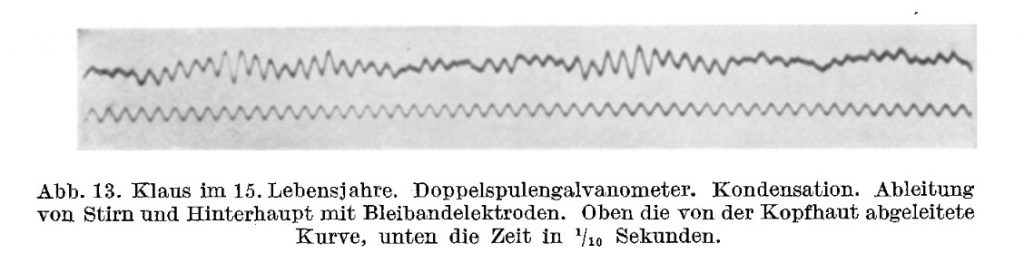

We’ve known for almost 90 years that rhythms exist in the human brain. In 1929, German psychiatrist Hans Berger recorded the first evidence of rhythmic brain activity by placing sensitive electrodes on the outside of his patients’ heads. When his patients closed their eyes, the electrodes recorded a rhythm going up and down ten times a second. When they opened their eyes, the rhythm stopped. Berger called this these bursts of rhythmic activity ‘alpha waves’, and neuroscientists still study them today.

From Hans Berger’s report: “Fig. 13. Klaus; aged 15. Double coils galvanometer. Condensation. Derivation of forehead and occiput with lead electrodes. Above the curve derived from the scalp, below the time in 1/10 seconds.”

But what is happening in the brain that produces alpha waves? When one neuron in the brain fires, it produces a tiny electrical signal, far too small to be measured outside the head. But when thousands of neurons fire at once, all the electrical signals add up and create a large signal. So large that we can measure it with our electrodes. Rhythms tell us that many neurons are working together. It’s like an orchestra; if every musician played a different tune, you would get chaos; if they all play the same tune, you get beautiful music.

A rhythm for every role

Fast-forward to the present day, and many more brain rhythms have been discovered. Just like in the natural world, there are fast and slow varieties, and each one seems to do a different job. For example, rhythmic activity at the faster ‘beta’ frequency is often present after a person makes a movement, and very fast ‘gamma’ activity is thought to be important for allowing different brain regions to collaborate. In my own work, I’ve shown that input from the regions in the front of the brain acts like the conductor of an orchestra, controlling what rhythms are active in other brain regions so they work together efficiently.

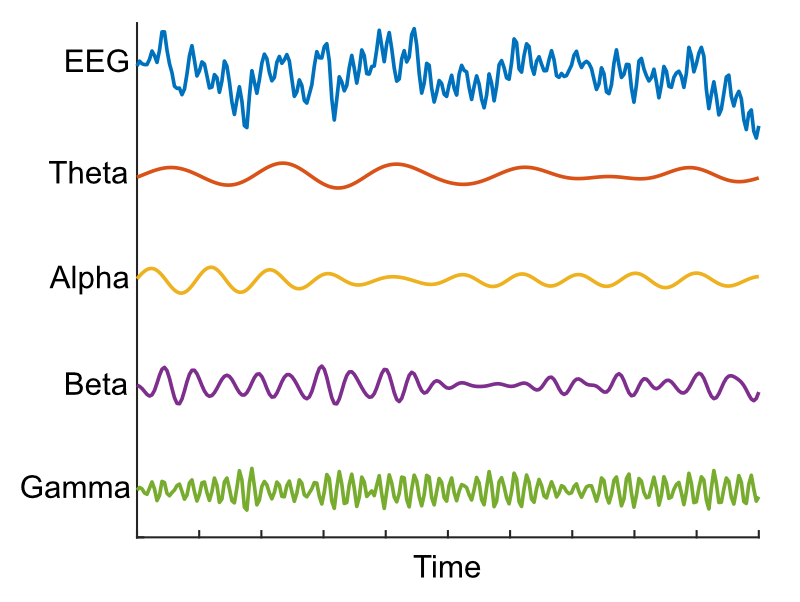

Image by Tom Marshall

Brain waves: On the top row we see some real activity from my own brain. In the bottom rows we see the different brain rhythms that are present in this activity. Notice how they come and go at different times? This could be a clue about when different processes are happening in the brain.

Dance to your own beat

Although we’ve learned a lot about brain rhythms, there are a lot of fascinating questions that we don’t yet have an answer to. For example, why the alpha rhythm is not the same in every person. Or, why some people’s alpha waves go up and down nine times a second, some ten, some eleven. Or why it slows down as a person gets older. A few people – I am one of them – hardly seem to have any alpha waves at all! Do we have a different kind of brain, or are the alpha waves ‘hiding’ somewhere that we cannot see with our neuro-imaging equipment?

Answering these questions might allow us to understand everyone’s personal orchestra affects their perceptions, experiences, or thoughts.

So just remember: Even if you can’t keep a beat, don’t worry – your brain is making its own unique rhythms.

Written by Tom Marshall, edited by Annelies

Tom Marshall is an alumnus of the Donders Institute and now works as a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oxford. Read more on www.tomrmarshall.com