This post is also available in Dutch .

You might have heard of the idea that people who are incompetent in something overestimate their own capabilities, while competent people underestimate themselves. This is also known as the Dunning-Kruger effect, named after the two psychologists who first described it. By now this effect has evolved to a well-known phenomenon and is often referenced. All that remains is the question whether the effect actually exists.

What is the original research about?

In the original paper of Dunning and Kruger (1999), 89 participants performed several tasks ranging from language and grammar to logic and argumentation. Afterwards, they had to estimate their own performance on a scale of 1 to 10.

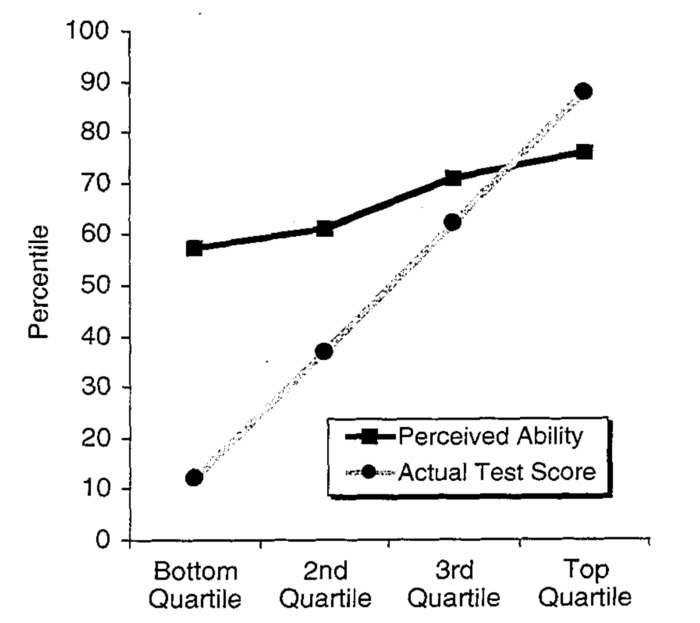

Then, the researchers compared the actual scores with the estimated ones. They did this separately for four groups: the 25% worst performing participants, the 25% best performers and the two groups that fell in-between. This led to the figure below, where you can see that especially the 25% worst performing participants seemed to overestimate themselves (their estimated scores were much higher than their actual scores), and the 25% best performing participants seemed to underestimate themselves.

Image from Dunning & Kruger (1999).

The researchers interpreted this as evidence that the brain is blind to its own incompetence, which is why we tend to wrongly estimate our own capabilities. Importantly, they emphasised that this effect does not specifically say something about ‘stupid people’, but about all of us: we all have our weaknesses and should all be aware of our fallacies.

But what’s wrong?

Although other researchers repeatedly found the same results, there are signs that the results are the caused by the way people had to estimate their own capabilities. Participants had to estimate their score on a scale from 1 to 10. You can imagine that making such an estimate is sensitive to errors: the first time it’s a little higher (for example 5.4), and the next time it’s a little lower (for example a 4.6).

What happens when you perform extremely well or extremely poorly? Someone who performs poorly (and gets a score of 1), and routinely underestimates themselves, cannot indicate a score of 0.5, because 1 is the lowest number on the scale. So, they indicate a score of 1. But poorly performing participants who overestimate themselves, will still give themselves a higher score (for example 1.5). Because of this, the average estimate of poor performers will be higher than their actual scores. The reverse occurs for people who perform very well: they cannot provide an estimate higher than 10, so the average estimate of the best performing participants is lower than their actual score. This is the pattern that Dunning and Kruger observed.

Everyone overestimated themselves

Still, this cannot fully explain the pattern found in the results. If you take into account that people with a low score cannot underestimate themselves, and people with a high score cannot overestimate themselves, it turns out that the participants in the original study appear to all overestimate themselves, regardless of their actual performance. This does not mean that all people always overestimate themselves: this doesn’t occur when, for example, a task is difficult for everyone. As you can see, it just depends on the context.

As far as I’m concerned, this shows how difficult research can be, and that we should all be careful with interpreting research results. The Dunning-Kruger effect is an example of how an apparently intuitive psychological finding can find popularity in society, but also lead an incorrect life of its own. Dunning and Kruger were right in that regard: we are all vulnerable to fallacies.

See also this explanation of what is and isn’t the Dunning-Kruger:

https://www.talyarkoni.org/blog/2010/07/07/what-the-dunning-kruger-effect-is-and-isnt/

Credit

Author: Felix Klaassen

Buddy: Marlijn ter Bekke

Editor: Ellen Lommerse

Translator: Wessel Hieselaar

Editor translation: Jill Naaijen

Featured image courtesy of Michal Matlon via Unsplash