This post is also available in Dutch.

Playing videogames can improve your well-being and may even help with recovery from trauma and other mental health challenges.

Many people associate videogames with violence and self-isolation, and it’s not unusual for the gaming subculture to have strong critics. But on the other end of the spectrum lie the most loyal supporters of video games. What creates the latter? And regardless of whether we identify as a gamer, what can we all find in the world of a videogame?

Gaming supports positive well-being

The benefits of gaming go beyond enhanced cognitive functioning and mental flexibility. Emerging research shows that moderate (7-10 hours per week) gaming improves individual player’s mental well-being, having a positive impact on their emotions, sense of accomplishment, and satisfying our need to feel competent. The emotional experience of a game, combined with the sense of agency it enables, can help players think and act outside the box and undo negative emotions – a strong component of building resilience. Furthermore, a study in adolescents concluded that videogames can be used as an experience-based learning method to promote emotional intelligence, the ability to understand one’s own and others’ feelings, regulate them, and communicate about them. Ever-evolving technology and greater use of virtual reality scenarios add an extra layer of realism and depth to the gaming experience, with players’ brain activity reflecting their sense of “being there.”

Can videogames be a part of therapy and help us heal from trauma?

The potential use of gaming as therapy has already been suggested a while ago by showing that playing “Tetris” in the few hours after a traumatic event might reduce flashbacks from the event later. Since then, many more intricate game narratives have been constructed, with storytelling and art elements capable of offering a deeply personal experience and a safe space for the player to deal with some of the most difficult emotions and traumatic experiences a person can have.

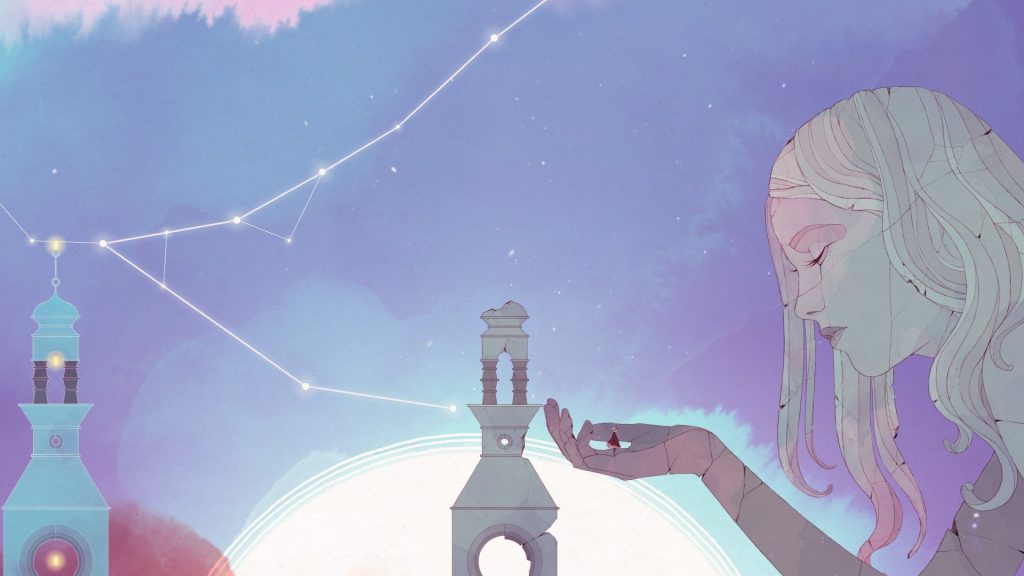

A noteworthy example is the immersive game GRIS which, through color, sound and its aesthetic design, helps the player deal with grief and recover from loss. Each level in the game is coded like a stage of grief according to Kübler-Ross’s five stage grief model, and as the story progresses, it gains a color that fits the stage. Through skill-based challenges, the player learns new ways to cope with their loss and come to terms with the new reality.

Another game praised for its accurate portrayal of psychosis, Hellblade: Senua’s Sacrifice, not only teaches coping skills through the eyes of a Celtic warrior, but was also found to reduce mental health stigma for those who played and identified with the main character by reducing their stereotypes and distancing from those affected by a mental disorder. There are many more games that take advantage of the unique qualities of this interactive medium and thus open up novel opportunities for aid in treatment processes. After all, there is a whole world out there, but there is also a whole world inside a videogame.

Original language: English

Author: Christina Isakoglou

Buddy: Rebecca Calcott

Editor: Marisha Manahova

Translator: Floortje Bouwkamp

Editor translation: Marlijn ter Bekke

Header image: screen capture during gameplay of GRIS, game by Nomada Studio.