This post is also available in Dutch .

After months of not seeing loved ones, you have to somehow suppress the urge to give them a hug when you see them – after all, the coronavirus is still among us. Controlling your emotional actions, for example, by not embracing friends and family, is challenging for everyone, but can be especially so for people who are dealing with anxiety. For example, people suffering from a social anxiety disorder show excessive avoidance behaviour in social situations, and have a greater chance of worsening symptoms as a result. Whereas researchers have previously used brain stimulation to reduce control over such actions, researchers at the Donders Institute have now also succeeded in improving that control. This new study is described below.

Automatic tendencies

The new study used a computer task in which subjects had to approach or avoid happy and angry faces with the help of a joystick. By nature, people tend to approach happy faces and avoid angry faces. This becomes clear when we ask subjects to do the opposite: avoid happy faces and approach angry faces. Because there is a natural tendency to execute certain actions in certain situations (e.g. approach-happy, avoid-angry), control over those emotional actions is needed to be accurate in situations that go against this tendency. The less control people use, the slower people react and the more mistakes they make in such “unnatural” situations. Fair enough, but how do you improve that control?

Amplification of brainwaves

Previous research has shown that control over emotional actions in the brain is particularly dependent on effective communication between two areas of the brain: first, the prefrontal cortex at the front of our brain, which controls other areas of the brain involved in emotion processing, and second, a part of the motor cortex, a region of the brain involved in carrying out emotional action.

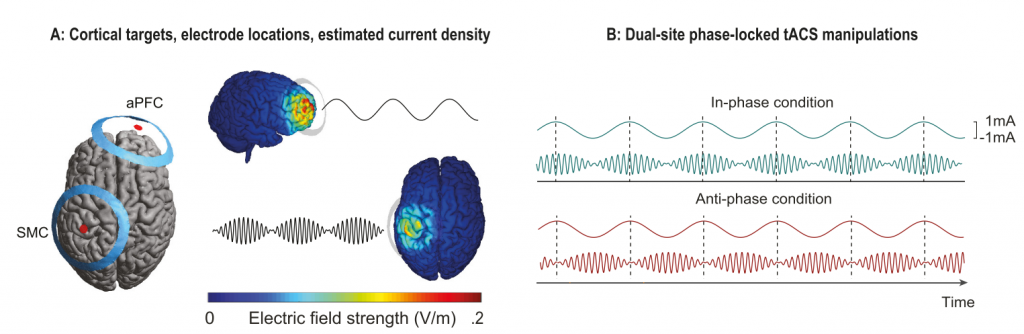

In order to be able to control your emotional actions, good communication between those two brain areas is crucial. Brain areas communicate by using brain waves, characterized by peaks and troughs. In the current study, the brainwaves in the prefrontal and motor cortex were controlled using a specific type of electrical brain stimulation called transcranial alternating current stimulation (tACS).

Peaks and troughs

This brain stimulation was carried out in two* conditions. In the first condition, brainwaves of the brain areas were amplified such that the peaks and troughs of the brainwaves of the two different brain areas matched exactly: this should improve communication between the two areas. In the second condition, brainwaves were also amplified, but the brainwaves of the two areas did not match: when one area was peaking, the other was dropping. Even though brainwaves of both brain areas were amplified, they were no longer properly attuned to each other.

Improved communication between brain areas leads to more control over emotional actions

The results showed, first and foremost, that matching the two brain areas led to better performance: the difference in performance between natural actions (e.g. approaching happy faces) and unnatural actions (e.g. approaching angry faces) became significantly smaller when communication between the two areas of the brain was improved. Thus, subjects succeeded in exerting more control over their emotional actions. The stronger the effect of the brain stimulation on a person, the better this person became at controlling his actions. It therefore seems that it is communication between the brain areas (and not so much the activation of individual areas) that is important for exerting control.

Brain stimulation as therapy?

All of this raises the question of whether this method can be used to help people who have difficulty controlling their emotional actions (such as anxiety patients). Before that stage is reached, it will have to be established how long this intervention has an effect on behaviour, and whether the findings generalize to other, everyday situations. In addition, the current research was conducted among healthy subjects; the researchers are therefore currently testing whether they can confirm their findings in people with social anxiety. For now, unfortunately, we are still entirely responsible for our emotional actions ourselves, but this research offers crucial insight into the functioning of the brain and shows how treatments can be expanded in future.

Credits

Original language: Dutch

Author: Felix Klaassen

Buddy: Floortje Bouwkamp

Editor: Jill Naaijen

Translation: Ellen Lommerse

Editor translation: Rebecca Calcott

Featured image courtesy of Melanie Wasser via Pexels

*There was also a third condition in which no stimulation was applied, but this is not relevant for the results discussed here.