This post is also available in Dutch.

October 10th was World Mental Health Day, an initiative that began in 1992 to raise awareness of mental health issues and fight social stigma surrounding the topic. Lots of research has shown that work conditions can have a negative impact on workers’ mental health. Recent years have seen an increase in attention for mental health issues in the workplace, and academia is no exception. In fact, the figures suggest that university researchers in general, and graduate students in particular, are more prone to experience mental health problems.

Mental health issues prevalent in academia

The prevalence of mental health disorders and symptoms among academics is so high that this year saw the first International Conference on the Mental Health & Wellbeing of Postgraduate Researchers, which quickly sold out. There’s even talk of a “mental health crisis” in academia, and there’s evidence to suggest that it’s not just talk: several studies done in Australia and the UK reported prevalence rates for mental health problems among academics between 32 and 53%, particularly depression and anxiety.

Some studies have found that these rates are even higher in younger academics. A recent study that surveyed more than 2,000 PhD and Master’s students from 26 countries revealed that graduate students were more than six times as likely to suffer from anxiety and depression compared to the general population. Of those who completed the survey, 41% scored as having moderate to severe anxiety and 39% as having moderate to severe depression, compared to 6% of the general population, in both cases.

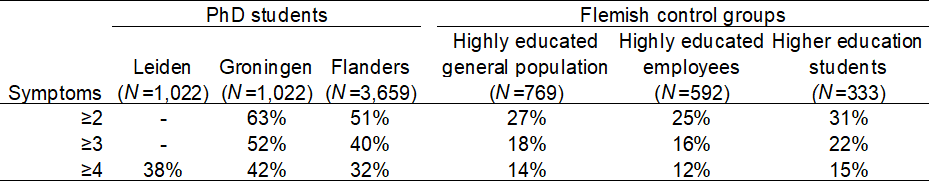

A little closer to home, another study assessed 3,659 PhD students at Flemish universities, as well as other higher education students, highly educated employees, and people from the general population with a higher education, for comparison. The results revealed that 32% of PhDs were at risk (?4 symptoms) of having or developing a common psychiatric disorder (mainly depression), while 51% reported experiencing at least 2 symptoms of mental health problems, which is usually an indicator of psychological distress. This was about twice as many as for the other groups, as can be seen in the table below. Similar figures have emerged from reports from Dutch universities in Amsterdam, Leiden, and Groningen, and the Max Planck Society’s annual survey found that two out of three PhDs indicated at least one of seven possible symptoms of stress linked to burnout (e.g., back pain, chronic fatigue, sleeplessness).

Prevalence of common mental health issues in Belgian and Dutch PhD students and comparison groups

Mental health issues measured by the General Health Questionnaire. N=sample size.

Table adapted from Levecque et al. (2017), van der Weijden et al. (2017), and van Rooij et al. (2019).

An inhospitable environment

More research needs to be done before we can understand what’s causing the high prevalence of mental health issues in academia. It could be, for example, that people who are prone to mental health problems like depression and anxiety tend to choose research careers. However, there is evidence of a link between the presence of symptoms and certain aspects of the work and organizational context of academia, including: high workload demands, insufficient funding and resources, job insecurity, lack of social support, insufficient recognition and rewards, and high work-life interference (lack of balance).

For PhDs in particular, work-life balance, high job demands, low job control*, and the quality of the relationship with the supervisor and how inspirational their leadership is have been found to be most associated with mental health issues. Furthermore, studies highlight a “culture of busyness,” where overworking is valued, and fear of stigma or professional risk which prevents many academics from actually seeking help. What’s more, a study done in the US with faculty who self-identified as having mental-health histories found that nearly 70% had no or little familiarity with the resources available to them.

In a competitive environment that values overworking, academics may be reluctant to seek help for fear of stigma and professional consequences.

Photo by Anthony Tran via Unsplash (license).

A ray of hope

The situation may look grim but the fact that more attention is being given to mental health issues in academia, and in general, is a good sign. In the US, a large research project is even underway to evaluate mental-health resources and support available for graduate students. Other proposed steps are mental health and emotional wellness training to help faculty and graduate students, and give them the tools to provide support to others; a change in the institute-wide culture to promote wellness; and anonymous surveys to assess mental health which can be used to offer counseling. For graduate students, additional focus is on providing healthy examples, establishing work-life balance and improving the relationship with the supervisor, given the important role it has been found to play in PhD mental health and satisfaction with the PhD in general. Suggestions have also been made for more higher level policy changes. Finally, it’s interesting to note that, despite the high rate of mental health concerns, surveys have found that most PhDs still love their jobs.

If you’re an employee at Radboud University or Radboudumc and would like more information about their services, you can contact the Occupational Health & Safety and Environmental Service (AMD).

*Job control is defined as decision authority and skill discretion (the levels of skills needed and the ability to decide which ones to employ).

This blog was originally written in English.

Author: Mónica Wagner

Buddy: João Guimarães

Editor: Christienne Gonzales Damatac

Translator: Felix Klaasen

Editor translation: Floortje Bouwkamp

Top photo by Thought Catalog via Unsplash (license).

Having been raised with two languages herself, Mónica Wagner is interested in how people use and learn multiple languages, especially when it comes to the sounds of languages. During her licence in psychology (National University of Córdoba, Argentina) she looked into whether people who speak two (or more) languages, when wanting to say the word for ‘dog,’ consider the name in both of their languages. Then, during her Master’s in cognitive neuroscience (Radboud University, The Netherlands), she looked at the other side of the coin: whether bilinguals can selectively listen in one of their languages (sometimes even the wrong one!) and the role of the context they’re in at the moment or whether or not the speaker has a foreign accent. Currently Mónica is working on her PhD at the Donders Centre for Cognition (The Netherlands), where she’s studying individual differences in foreign accent, that is, why some people struggle so much to get rid of their foreign accent in a second language, while others seem to be able to acquire a nativelike accent almost effortlessly. She is new to the Donders Wonders team but will likely blog a lot about her favorite topics: languages, bilinguals, and accents!