This post is also available in Dutch .

Don’t you hate it when you can’t remember a word you know you know? What causes this and why do we seemingly remember the words out of nowhere?

You’re trying to think of a word — you know the meaning and can think of synonyms, you might even know how many syllables it has, what sounds it starts with, or what other words it sounds like — yet you can’t for the life of you remember the word! The official term for this frustrating experience is tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) state, from the phrase “it’s on the tip of my tongue.”

TOT phenomena are universal, occurring regardless of language (even in sign language!), sex, or age. They’re actually quite common. According to some estimates, young people experience 1-2 TOT states per week, while older adults can have as many as one per day. While the occasional TOT state is normal, serious issues finding words can be a sign of anomic aphasia, a neurological condition characterized by severe problems recalling words, despite being able to describe or define them. Researchers are fascinated by TOT states because they can tell us a lot about how we remember and produce words.

Putting tip-of-the-tongue states under the microscope

The first experiments of TOT states were carried out by scientists at Harvard in the 1960s. They read out definitions of uncommon English words and asked people to recall the words, producing what they described as “mild torment, something like the brink of a sneeze.” Don’t worry — the researchers eventually told the participants the word, but not before confirming something your own experience may have shown you: TOT states are not illusions; very often the clues we come up with about the sought-after word turn out to be accurate.

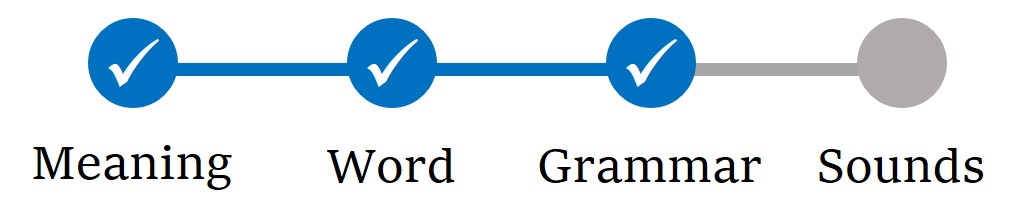

Many believe TOT states to be a natural byproduct of how we speak. The different information about a word — such as its meaning, grammatical category (e.g., noun, adjective), and sounds — are stored separately and accessed in that order when we speak. TOT states would then be as if the search of our mental dictionary got stuck at the stage where it was looking for the sounds.

Image by Monica Wagner.

It is unclear why TOT states occur, but there are several possibilities. One is that the target word is not “strong” enough for the search to make it to the sound level, such as with words that are infrequent or haven’t been used recently. Another explanation is that those other similar sounding/meaning words we think of end up “blocking” our search. It’s kind of like trying to remember something when people are shouting other stuff at you.

And all of a sudden it hits you

Perhaps the most curious thing about TOT states is how they seem to resolve themselves. You may have given up on remembering the word and gone on with your life when, all of a sudden, out of nowhere, it comes to you! Following the blocking view, these “pop-ups” could result from the alternative words “calming down,” giving us access to the target word. Another view is that we eventually stumble upon something that triggers the sounds enough to reach our consciousness.1 Whatever the reason, what a relief when the word finally comes to us!

Written by Monica Wagner and edited by Julija Vaitonytè.

1In a nice experiment demonstrating this, people were asked to come up with the word (e.g., “biopsy”) after being read its definition. When they experienced a TOT state, they were shown a picture to name. The pictures had two alternative names (e.g., “bike” vs. “motorcycle”), the less frequent of which began with the same syllable as the target word. Half of the time participants saw pictures like this, and the other half they saw pictures with unrelated names, like “helicopter.” The researchers found that people were more likely to come up with the target word “biopsy” after saying “motorcycle” than when saying “helicopter,” the idea being that “motorcycle” activated “bike” which helped reach “biopsy.”