This post is also available in Dutch .

After limb amputation, people often experience pain in their lost limbs. Scientists propose a brain-based explanation for why that is the case.

Even when a limb is amputated, people can still feel limb-related pain.

Credits: Air Force photo by Master Sgt. Adrian Cadiz (License CC0).

What is phantom pain?

Phantom pain is pain or a sensation of a body part that does not exist anymore, i.e., if a limb was amputated due to an accident, a person can feel it as if it were still there. People can experience phantom pain also in organs removed due to surgery such as breasts, eye, or tongue. Half of amputees experience pain in their lost limbs; however, the pain varies greatly across individuals.

Phantom pain is associated with preserved function of former hand area

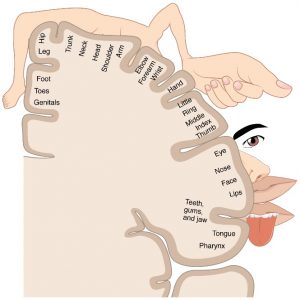

What causes phantom pain? According to previous theories, phantom pain occurs because of a mechanism that is called “maladaptive plasticity”. This means that after amputation, e.g., of a hand, the brain area that is involved in the processing of hand movements or sensations starts to react to activations from neighboring cortical areas(like lips; note from the picture below that lip and hand area are “neighbours”). This can potentially trigger pain representations related to the hand.

Brain area involved in processing hand movements (“hand area”) is situated quite close to the “lip area”.

Credits: Anatomy & Physiology, Connexions (Licence CC BY 3.0)

Recently, an alternative explanation to phantom pain has been proposed. A group of researchers from University of Oxford showed that phantom pain was associated with preserved activity in the brain area that represents the body part that was amputated (in case of a hand amputation this would be the brain area responsible for hand movements).

During an fMRI experiment, amputees with one hand were asked to imagine moving their missing hand, while people with two hands performed the actual movement. Amputees activated phantom-related brain regions (in somatosensory cortex) similar to the ones found in two-handers. That means that hand-related brain representations were still preserved, even after 18 years of amputation. In addition, the amputees with the worst history of phantom pain showed the greatest brain activation during phantom movements.

To check if the “maladaptive plasticity” theory holds, researchers verified if the information about lip-movements can be found in the “phantom-hand” brain region. Therefore, participants were asked to perform lip-smacking movements in addition to imagining hand movements while being in the scanner. Researchers showed that the hand area (after amputation of the hand) does not respond to inputs from other cortical regions such as lips.

After a hand amputation, the brain area related to hand movements loses its sensory input because the information from the external world is not fully available anymore. However, the information about the hand is preserved for years to come. Importantly, the fact that the “hand area” is silent to the neighbouring area’s input suggests that the input received by the neighbors can’t trigger pain representations either. This finding opposes the theory of maladaptive plasticity and describes potential mechanisms underlying phantom limb pain.

Written by Lara. Edited by Mahur.

Read more about phantom pain here https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19506071