This post is also available in Dutch .

The very first experiment that researched why you’re unable to tickle yourself stems from 1971. Researchers from Cambridge built a tickling-machine so that participants could tickle themselves or they could be tickled by a researcher. In both instances, the tickling-machine gave the exact same tickles. Still, the participants felt a much stronger ticklish sensation when the researchers operated the machine than when they did it themselves. What’s up with that?

Expectations

The most common explanation has to do with expectations. The main idea is that unexpected contact feels stronger than expected contact. If someone else tickles you, you won’t exactly know where, when, and with what intensity you will be touched, but when you do so yourself, you do know. The results of a study in which participants where tickled while they were inside an fMRI machine supports this explanation. When participants tickled themselves using a tickle-machine, the somatosensory cortex – a region of the brain that processes bodily experiences such as touch – was less active than when the researchers piloted the machine. This explains why tickling feels less like tickling when you do it to yourself.

How expectations influence our perception

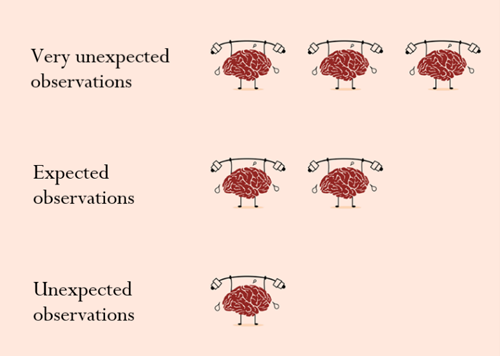

Does this mean that your brain suppresses aspects of the environment you expect and instead you perceive what you do not expect? Not completely. A recent proposal suggests that it works as follows. Our perception has two important functions: ensuring that what we perceive is accurate – that what we perceive matches with reality – and ensuring that what we perceive is informative – that we perceive things from which we can learn. Our perception becomes more accurate because we have many expectations about the way the world works. Imagine you’re at work and you see some vague figure waving at you. You’re more likely to expect that it’s a colleague than an old friend from high school. On average, such expectations make our perception more accurate. Therefore, in general we process expected aspects of the environment more strongly than unexpected ones; it helps us to be more accurate. But it’s also very important to perceive things correctly when something very surprising happens – that makes the observation informative. For very unexpected occurrences, our perception is therefore even stronger. You process those even more strongly than expected observations. Based on these very unexpected observations, your expectations for next time slightly change: you’ve learned!

Can you become immune to tickling?

If we apply this knowledge to tickling, we must conclude that being tickled by someone else is so unexpected that we perceive it extra strongly (see the top row of the above image). We perceive it more strongly than when we tickle ourselves (the middle row of the image). But shouldn’t we learn from this? In any case, I know one thing for sure: I haven’t been able to become immune to tickling, unfortunately…

Tip: This episode (in Dutch) with Professor Floris de Lange of the Donders Institute about the brain as a prediction machine.

Credits

Original language: Dutch

Author: Marlijn ter Bekke

Buddy: Felix Klaassen

Editor: Jill Naaijen

Translation: Wessel Hieselaar

Editor translation: Marisha Manahova

Image from Ketut Subiyanto via Pexels