This post is also available in Dutch .

We all know that diet is an important part of our physical health. In previous blogs we’ve even discussed the interaction between our diet and the brain and, thus, mental well-being (e.g., here and here). But did you know that even the presence of certain sounds in our languages can be traced back to our prehistoric ancestors’ diets? That’s what a study published recently in Science shows.

Diets, overbites, and labiodentals

The sounds we can make are limited by our speech organs and thus influenced by changes to the latter. If you’ve ever had to wear braces or some other type of dental device, you might remember how these made you talk funny at first. The new study, by an interdisciplinary team of researchers from around the world, provides evidence that changes in our bite due to changes in diet may have introduced new sounds into early humans’ language. These new sounds are the labiodentals: sounds made by contact between the upper teeth and lower lip, such as ‘f’ and ‘v’. But what does diet have to do with it? you may ask.

Most human babies are born with what are known as overbite and overjet; that’s when your upper teeth fit over your lower teeth. Apparently, before the Neolithic period (approx. 12,000 years ago), when we were all hunter-gatherers, tooth wear from having to chew tough, uncooked food would cause a change in bite configuration by adolescence, with the (now shorter) front teeth sitting snug atop the bottom row (what is known as an edge-to-edge bite). However, recent anthropological evidence suggests that changes in food production that came about during the Neolithic, such as farming, cooking, and food storage, brought about soft food diets that allowed overbite and overjet to remain past adolescence.

Image by Nielson2000 via Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 3.0).

The languages of hunter-gatherer societies have less labiodental sounds

In 1985, linguist Charles Hockett proposed that the languages of contemporary hunter-gatherer societies showed a marked lack of labiodental sounds because these are harder to produce with their diet-induced edge-to-edge bites. The new study is the first to provide strong evidence for this claim.

Using biomechanical simulations, the international team was able to show that producing labiodentals in the overbite and overjet configuration is a lot easier than with an edge-to-edge bite, requiring less movement of the muscles in the face and mouth. You can test this yourself by seeing how much you have to move to produce an ‘f’ sound in both starting configurations.

The study also tested another aspect of Hockett’s theory: that the languages of hunter-gatherer societies have less labiodentals. They indeed found that hunter-gatherer societies (e.g., native populations in Greenland, southern Africa, and Australia) have only around 27% the amount of labiodentals food-producing societies do. What’s more, by analyzing languages within the Indo-European family, the authors were also able to show that there has been an increase in the presence of labiodentals over time, likely starting around the time that dairy and cereals became a staple in Indo-European diets. Today 76% of existing languages have labiodentals.

Language researchers have long thought that the sounds we can make are biologically determined and have remained unchanged since thedawn of humanity. These new findings are exciting because they suggest that cultural innovations, such as food technologies and our diet, may have changed how our languages sound today.

A nice video overview of the study: [youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SWceBh08pL8&feature=youtu.be]

Written by Monica Wagner and edited by Julija Vaitonyt?.

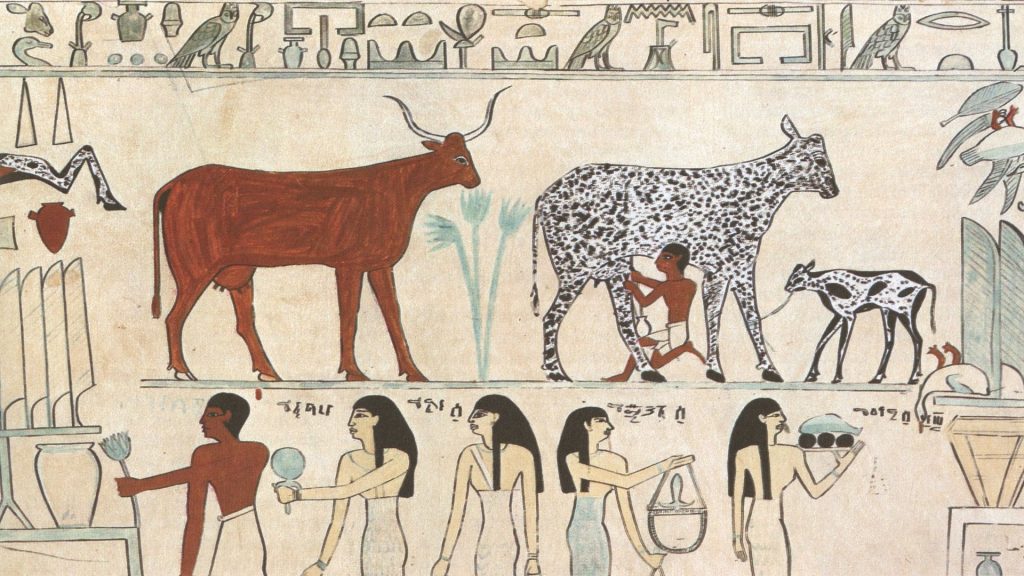

Featured image: Old Egyptian hieroglyphic painting showing an early instance of a domesticated animal (cow being milked).

Scanned from 1000 Fragen an die Natur, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1948. Via Wikimedia Commons (public domain).