This post is also available in Dutch .

We all know the common “less is more”. Apparently, we all need to be reminded that sometimes it can be better to delete something rather than to add it. But is this really the case?

Delete vs. add

In a recent study, scientists conducted a series of experiments to find out whether people are inclined to make changes by adding, rather than deleting, things.

Subjects were shown a grid with a colored box pattern on their computer screen. The assignment was to make the displayed pattern symmetrical by removing or adding cells. While it was equally easy to add versus remove cells, the vast majority (80%!) chose to add cells.

The same was true when subjects had to adapt block structures of Lego as well as essays and schedules. Only when there were clear indications that deleting was better than adding (e.g., by rewarding deleting) did people have less of a tendency to add things.

What’s more, people seem to do this in everyday situations too: The researchers found that fresh college presidents suggested making subtractive versus additive changes in their new plans in just 11% of cases.

Is deletion overlooked?

How come? Do we think adding is better, or are we overlooking the option to delete?

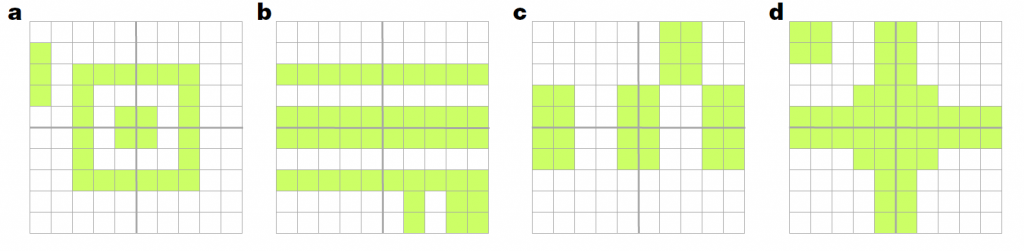

To find out, the researchers got a new group of participants to do a modified version of the grid game. The participants now had to make the grid both horizontally and vertically symmetrical in as few clicks as possible. The grids were further developed in such a way that it was objectively better to remove rather than to add cells (see image).

In addition, some of the participants were given the opportunity to arrive at a solution for four different patterns (a-d) (without feedback), while the rest of the participants were only shown the last pattern (d).

Indeed, this showed that the group that was first shown the three other grids chose more often to remove cells from the last grid than the group that was shown the same grid without the predecessors. If people thought adding in itself was better than deleting, there should be no difference. So, people initially seem to overlook deletion and have to learn that it may be the better option. In other words, you must – and can – learn to delete.

Credits

Author: Felix Klaassen

Buddy: Jeroen Uleman

Editor: Floortje Bouwkamp

Translation: Jill Naaijen

Editor translation: Marisha Manahova

Featured image courtesy of Pixabay via Pexels