This post is also available in Dutch.

There are so many things to research: medicine, rockets, farming methods, all with clear goals in mind. But what about “basic research?” Could it be just as important?

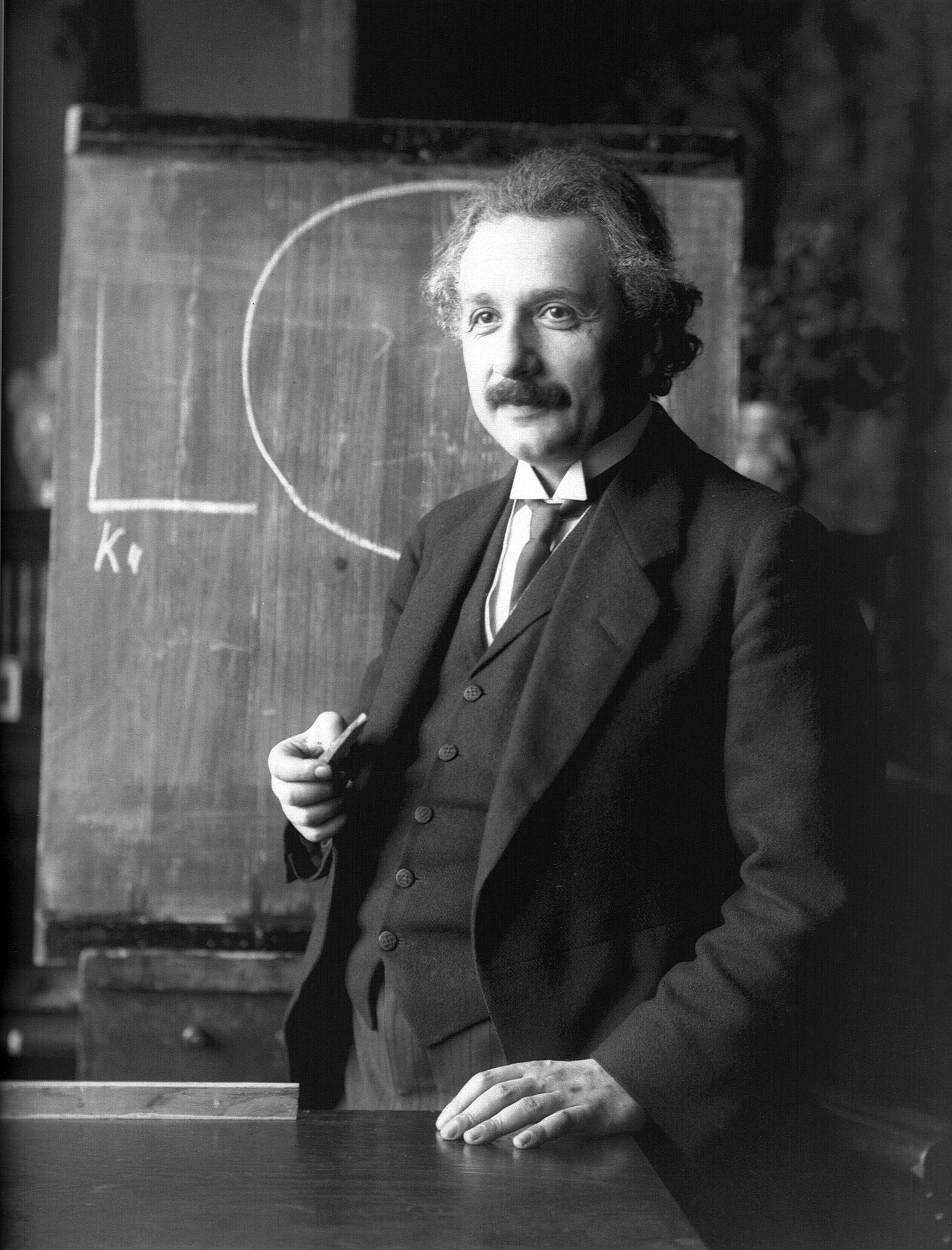

Just as the GPS wouldn’t have been possible without Einstein’s theory of relativity, basic research can set the ground for important breakthroughs and technological advances.

Image courtesy of Pixabay (CC0).

As a scientist in the field of psycholinguistics (the psychology of language), people are often quite curious about what I do. After a brief explanation, most even find it pretty interesting. But then comes the question every basic researcher dreads: “Why?” What’s the point of researching this? And that’s where things get sticky.

Two years into my PhD and I still find myself scrambling to answer this apparently innocent question. I used to give a few examples of how my research could be used to solve important problems, but lately I’ve settled on another approach: “Do you know what basic research is?” I ask.

Not all research is applied research

I think the confusion stems from the fact that most people equate research, in general, to “applied research.” But applied research is actually just one type of research which is done, well, with the applications in mind: its goal is to come up with a practical solution for a specific problem. Research into cures for a certain disease or developing an engineering solution are examples of applied research.

On the other hand, you have what is called basic or fundamental research. This is research whose sole purpose is to research: to find out how things work, extend our knowledge, develop and test theories. That’s not to say it’s necessarily just theoretical or that the research questions aren’t tied to everyday problems. For example, my research focuses on understanding why some non-native speakers have a stronger foreign accent than others. I run experiments to try to answer this question, which has clear practical implications…but actually thinking of those implications is not part of my job. But why do I always sense a hint of disappointment when I say this out loud?

The unforeseeable implications of basic research

You may wonder how researchers can get paid (usually from taxpayers’ pockets) to seemingly “fiddle around.” But basic research is essential to advancing science. Understanding how things work is important for coming up with more applied solutions. Imagine scientists trying to develop a medical treatment without a proper understanding of the human body. It’s good to have implications in mind, but we can’t always know what developments new knowledge will lead to. In fact, a large part of technological solutions were made possible by basic research. A classic example is GPS, which exists thanks to Einstein’s theory of relativity. But this isn’t just an exception: a study that examined 4.8 million U.S. patents and 32 million research articles found that as much as 80% of the articles were linked to a later patent. So most research does contribute to new developments, most likely ones the authors couldn’t even have imagined.

We all had to learn things in school we thought were useless. But most of those things came in handy later, if not directly then indirectly by helping us understand other ideas more quickly. It’s the same with science. We don’t know what the future will hold, so we’re just trying to understand as much as possible. Someday maybe our findings will help us or someone else make a big breakthrough.

Written by Monica Wagner and edited by Annelies van Nuland.

To hear more about the value of basic research, watch Roshan Cools’ Ted Talk on trusting science: