This post is also available in Dutch.

It is one of the oldest debates in psychology: Is our behavior shaped by nature or by nurture, that is, by genes or by environment? Since I study how genes and the brain contribute to psychiatric disorders, it is often the start of a conversation about my work. Usually, I answer rather vaguely that both nature and nurture are important and they are mutually dependent, like chicken and egg. But this explanation merely replaces nature with eggs and nurture with chickens, and it does not justify how deeply intertwined processes in our brains, genes, and environments are.

Illusions of deterministic nature and controllable nurture.

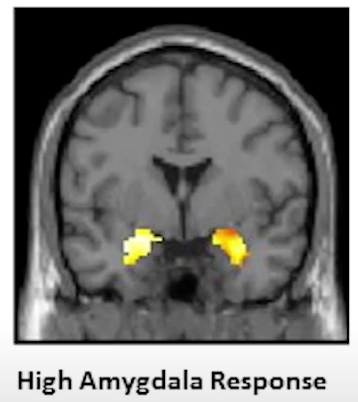

Nature is often intuitively associated with determinism, the idea that actions and thoughts are pre-determined and inevitable. On the other hand, nurture tends to be more associated with controllable and avoidable environmental factors. As a result, the nature-nurture debate has consequences for stigma, and for feelings of empowerment for patients. However, the intuitive associations of nature with determinism and nurture with flexibility are misleading. When neuroscientists show a blob of activation in the brain associated with anxiety, someone may feel as if their anxiety is inevitable and hard to cure because it is engrained in the brain. Yet, when the same person has a nosebleed, a picture of their bleeding nose will not generally make them feel helpless. When a geneticist points out that depression is highly heritable, someone may conclude that depression is “in their DNA” and therefore its course and severity are pre-determined. However, which kind of milk you drink is about as heritable as depression, and yet few people feel destined to drink semi-skimmed milk just because it’s in their DNA.

The chicken-egg scramble

Nature and nurture are not exactly like chicken and egg, but more like one big chicken-egg scramble that simmers continuously throughout our lives and is stirred and seasoned all the time. The genetic and environmental influences on behavior interact and correlate with each other. They interact, for example, because an environmental factor, such as stress, may only cause a disorder for people who are already genetically vulnerable, but not for people who are genetically more resilient. And genes and environment correlate, for example, because stressful life events are in part driven by the same genes as the disorders themselves. In that case, a gene may cause a psychiatric disorder because it makes a person more likely to choose or encounter a stressful environment. This means that risk genes for these disorders act not only via molecules and neural circuits within our body, but also via our attitudes and lifestyle preferences by which we shape our environment.

Knowing this, the first thing we as neuroscientists ought to do to is accept the complexity of the nature-nurture scramble. Once we accept that it is impossible and irrelevant to completely separate the chicken from the egg, we can instead start identifying which different bits of chicken and egg influence each other and how. The recent revolution in genome-wide association studies, and new inventive methods to analyze complex links between genes and our brain, are giving us new and better ways to do this. For example, environmental factors such as education, stressful life events and diet are increasingly included in genetic studies, together with psychiatric disorders, to identify shared and distinct risk genes for both. Also, new methods allow us to “group” genetic effects based on how they influence the brain, or which protein interactions they impact, or which tissue they are most relevant for. These different gene-groups may point to more distinct mechanisms within the body and outside the body. For example, one group of genes may directly encode stress hormones (i.e. direct effect), while another group of genes is associated with the personality trait “openness to new experience”, causing one to encounter more stressful events (i.e. indirect effect). In these ways we can better trace more specific potential routes from molecule to brain to environment, and back(!). Although we will not suddenly unravel the huge knot of all possible ways in which genes, brains, environment and behavior influence each other, these are exciting times to disentangle some important threads.

Credits

Author: Emma Sprooten

Buddy: Felix Klaassen

Editor: Jill Naaijen

Translation: Emma Sprooten

Editor translation: Rebecca Calcott

Featured image courtesy of Grace O’Driscoll on Unsplash