This post is also available in Dutch.

In two recent blog posts, Lieneke told us a lot about habits. But you may be wondering: how does the brain implement habits?

Let’s say that when I come home from work (condition), I eat a chocolate-chip cookie and enjoy the sweet taste (outcome). Over time, my brain learns to associate coming home from work with the action of eating a cookie and with the reward of the sweet taste. This is how habits are formed: when actions become associated to certain conditions because the conditions repeatedly lead to a specific outcome. This is also called “conditioning.”

How the brain forms associations

Neurons communicate with each other by sending and receiving molecules called neurotransmitters, and dopamine is a neurotransmitter that is heavily involved in the way the brain processes rewards. Before I’ve formed the habit, dopamine-producing neurons in my brain become active when I’m eating a cookie because that’s when I’m experiencing the reward. Later, however, if I continue to have a cookie after work, those same neurons become active when I get home even before I’ve starting eating the cookie. This is because those neurons now predict the outcome. The conditions (arriving home) become tightly associated with the reward (eating sugar).

Two brain systems involved in habits

Once the brain learns the association between coming home and eating a cookie, the behavior becomes automatic and you don’t need to actively make a choice to carry out the action. This automatic association between conditions and behavior involves the limbic system, a group of brain areas in the center of your head. It is an older, preserved brain structure for basic survival functions (‘when you see something delicious, eat it, so you don’t starve’).

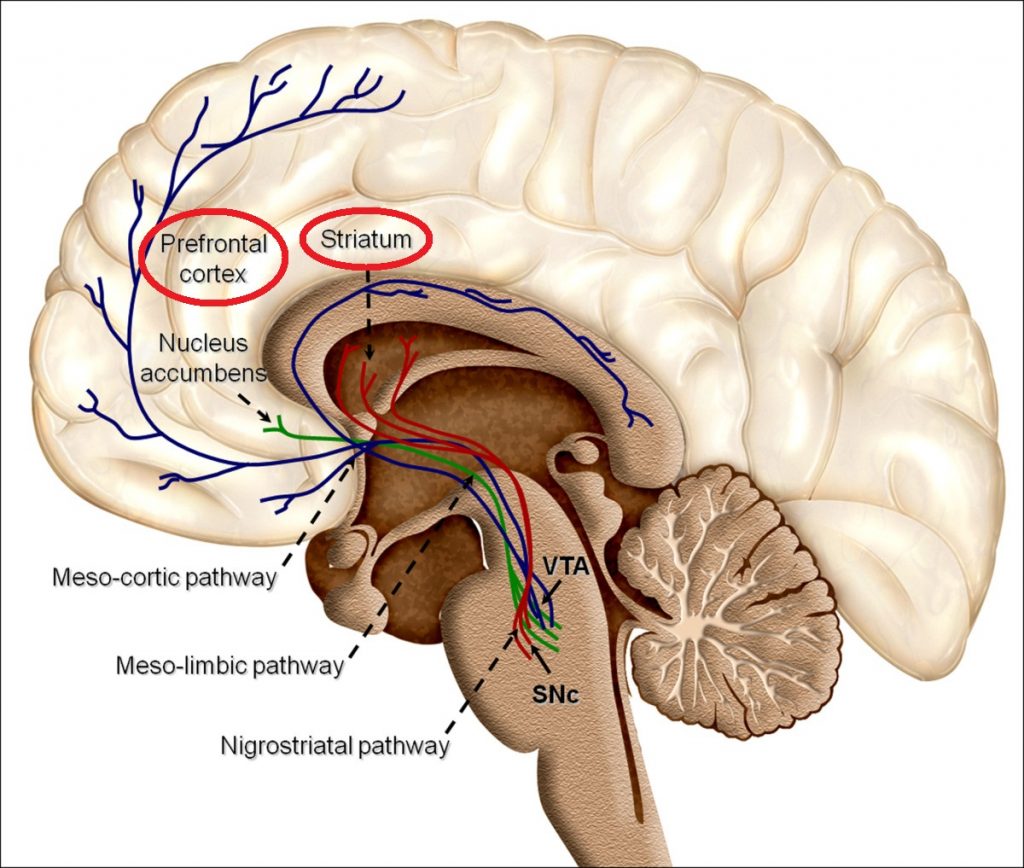

The striatum, a part of the limbic system, and prefrontal cortex are implemented in habits.

Image credits: Wikipedia (CC BY 3.0)

But nowadays we are not constantly facing starvation, so we may want to align our behavior with other goals. For instance, if you want to reduce your sugar intake, you may prefer to not eat that cookie after you come home from work. However, this can be difficult: if the automatic association in your brain is already set up, it will require effort to not act according to it. You will need to engage your cognitive resources and specifically your prefrontal cortex, a part of the brain at the front of your head. The prefrontal cortex is associated with cognitive control, e.g., controlling your urges and thinking rationally about your actions.

In order to engage your prefrontal cortex and control the urge to eat a cookie, you also need to pay attention to your feelings and actions. If you are rushing when you come home and are not paying attention, you may mindlessly eat a cookie and not even notice it. Therefore, it helps to be mindful of your actions. Once you notice you are about to reach for the cookies, you can pause and ask yourself if you want to act otherwise.

For Lieneke’s tips on how to change your habits, read this blog post.

Source: Lieneke’s PhD thesis.

For good information on the theory behind different systems in the brain, check out this post.

Written by Marisha. Edited by Roselyne.